James Branson.

There’s no other way to say it: in terms of quality, 2025 has been a lacklustre year for bigger-budget, government-funded feature films in Australia.

Don’t get me wrong, we’ve seen some great commercial films in general release and on the festival circuit, like Birthright, We Bury the Dead, Ellis Park and Beast of War, which are all top-tier. But as for some of the others, I’d go as far as saying that 2025 has been the worst year for high-end Australian films in decades.

The big stars have all headed overseas, funding bodies are too quick to back mediocre films, scripts are feeling rushed, feature films are beginning to feel like content for overseas streamers, and to make it worse, audiences have turned their backs on the cinema-going experience.

Thankfully, it’s not all doom and gloom. There’s still a shining light in the form of hard-working, blue-collar independent filmmakers in Australia who continue to do all the heavy lifting, making some of the most memorable and impactful films of the year. Films like Moonrise Over Knights Hill, Within the Pines, Carnal Vessels, Two Ugly People and A Grand Mockery are the ones that have stayed with me.

And now, there’s Bunny.

Written and directed by first-time filmmaker James Branson, Bunny is an atmospheric post-apocalyptic nightmare set in the aftermath of a climate collapse. Bunny (played by Kate Wilson in an impressive debut performance) roams the ruins of a world she never got to grow up in. Raised on scavenged books and B-movies, Bunny lives alone in an old shack she once shared with her father. Supplies are scarce, food is running out, and there’s nothing left to hunt except other people.

Bunny is a violent film that manages to be both meditative and nail-biting at the same time. Whether that’s by accident or not, it’s a noble accomplishment for Branson, who had never stepped foot on a feature film set before. Prior to making Bunny, Branson had spent most of his professional life working in commercials, but you’d never know it going by the quality of this film.

After 13 years of running Cinema Australia, my appreciation and adoration for independent filmmakers in this country remains at an all-time high, especially when I interview filmmakers like Branson who oozes confidence and beams with that can-do attitude that Australians are famous for.

If you’re in Sydney, you can catch Bunny at SXSW this week. If you’re elsewhere, be sure to keep an eye on cinemaaustralia.com.au for upcoming screening announcements.

Andy Golledge as The Father and Kate Wilson as Bunny in Bunny.

“I’m obsessed with the Mad Max universe. I just love it. It’s such a great playground for stories.”

Interview by Matthew Eeles

I first discovered you on TikTok, where you offer and request independent filmmaking advice. How has that community assisted your growth as a filmmaker?

Well, I learned most of what I know about filmmaking online, initially through YouTube and TikTok. I think I’m still in the early stages of building that audience, and I’ve only been making content for that page for about three months. But one thing I’ve noticed on TikTok, YouTube, and in those filmmaking communities is this obsession with gear and equipment, and less of an obsession with directing, acting, production, and how to find a location — all that sort of stuff. So it’s been great to discover that there’s an audience for that kind of thing, especially around Australian films. I think the video I made on TikTok that has the most views so far is one where I simply asked a question: where are the Australian movie stars who are starring in Australian movies at the moment? I wondered why that is, and how we might get back to that place where someone like Heath Ledger was a huge movie star but would still make films like Candy. I think it’s unfortunate that someone like Milly Alcock is in a huge film like Superman and the upcoming Supergirl movie, but isn’t acting in Australian films. So yeah, it’s been wonderful getting to know the TikTok filmmaking community in Australia and the people who are interested in local films, and realising that there are a lot of people here who genuinely care about it.

Is it correct that Bunny is your first-ever film? There were no short films or any other film work before it?

Bunny is the first piece of fictional content I’ve ever made. I made a documentary about four or five years ago that might see the light of day at some point. The subject is currently in jail. I spent most of my career making non-fiction content. I started out in media as a journalist and ran a magazine, which I was also the editor of. That magazine had a YouTube channel, so we made a lot of those Vice-style short documentaries. That eventually parlayed into making content for brands. Then I did this very strange documentary about a cult that lived in Armidale, New South Wales, which might also see the light of day at some point. But yeah, Bunny is the first piece of fictional content I’ve ever made.

What was that magazine?

It was called Sneaky.

Did it fold?

It folded, yeah. It was a magazine. Print is dead. It’s dead. Although, funnily enough, if I were to start a publishing business right now, I think I’d probably go back to print. [Laughs]. It’s so much better than digital. I’d been thinking about making a film for a long time, and every time I shot something — like an ad or a short documentary — I was always learning from those experiences so I could apply that knowledge to a feature film. I never thought I could write a short film, to be honest. I didn’t know if I’d be able to tell a ten-minute story that would satisfy me. I’ve never been able to wrap my head around short films. I want my stories to be fully fleshed out and really satisfying — and for that to happen, they need to be long.

Kate Wilson as Bunny in Bunny.

It’s admirable that you felt confident enough to jump straight into a feature. And I’ve seen Bunny, so you’ve certainly pulled it off. But why such an ambitious launch?

I don’t know if “ambitious” is the right word — “stupid,” maybe. [Laughs]. I’ve spent most of my adult life just jumping in the deep end of things, and I’m a pretty confident person creatively. I didn’t feel much doubt until we started shooting. I went in thinking, “Oh, I know exactly what I need to do. I know how to do this. I know what every scene needs to be. I’ve got it all down.” And then as soon as cameras rolled, I went, “Okay, this is harder than I thought it would be.” [Laughs]. There were some real challenges I didn’t anticipate during the making of this film. But I had some really creative and wonderful people helping me. That’s one of the strengths of filmmaking — it’s not all on you as the director. If you hire the right people, like a great cinematographer, lead actor, sound person, production designer, and producer, it’s not as hard as people might think, provided everyone’s talented. And we were really lucky. We got some incredibly talented people who were all working on their first feature film. The only person on this film who had ever made another feature was our producer, Taylor Thompson, and that was ten years ago when she lived in America. So yeah, I was really blessed with the cast and crew I had — very lucky. Because if I’d been relying solely on my own talent to make the film, it probably would’ve been a disaster.

Am I correct that Bunny took just seven months from its initial story conception to its first festival screening?

I wrote Bunny in August 2024, we shot it in December 2024, and it was edited and submitted by around April 2025.

Did you rely on anyone for script advice while writing the film?

I had some friends I’d worked with previously that I ran the script by to get their thoughts. But no, I was pretty confident in the script, actually. I was really pleased with it. I thought it had meaning and that it was pretty good. I kind of just dove in headfirst. I didn’t really overthink it before we started making it, to be honest.

I love your confidence. I’ve interviewed hundreds of filmmakers over the years, and I can’t remember one as confident in their skills as you.

There’s no other way to be.

Was there a reason you wanted to explore the post-apocalyptic survival subgenre?

I’m obsessed with the Mad Max universe. I just love it. It’s such a great playground for stories. I love the original Mad Max, and I think Mad Max: Fury Road is the greatest film ever made. I was very inspired by that world and also by the low-budget post-apocalyptic films that followed the original Mad Max. I love that world because you can tell a very contained story and imply a larger world beyond without requiring a massive production budget. Australian landscapes already look pretty dry and desolate on their own — although two weeks before we shot Bunny, it rained for the entire two weeks at our location, so it went from being really dry to suddenly lush and green, which was a real challenge. [Laughs]. But yeah, I made this film because I was really inspired by the Mad Max universe, and I wanted to think about how other people — not Mad Max or the central characters — might approach survival in that world. I wanted to explore the early stages of an apocalypse, not thirty years later when everything’s gone, but six years later. What’s happening to society as it begins to fall apart? That kind of thing.

Kate Wilson as Bunny in Bunny.

Bunny’s themes are surface-level. They don’t run extremely deep, and that’s not a negative thing. Can you talk us through some of the themes you do explore through this film?

You’re right. And I didn’t really think about the themes when I was writing Bunny. I was inspired to write a story in this post-apocalyptic universe and to think about the kinds of characters I’d like to introduce into it, and what we could fit into a minuscule budget.

As I was writing, some of the themes revealed themselves without me realising. On the surface, there’s obviously stuff about survival and how you survive in a world that’s gone to shit. But beneath that, I think there are ideas about the relationships between men and women and the ways men try to control women. Bunny meets three male characters, and they all try to control her in some way, some more overtly than others. It’s also about the ways women resist that control and how they express frustration, grief, or hunger differently from men. Later, I realised the film is also about the experience of having a teenage daughter. I’ve got a teenage daughter, and it became apparent once it was pointed out to me that I was writing about my own relationship with her, especially in the second act of the film, where Bunny spends time with her father. That’s really about my daughter and me.

As someone who had never made a feature film prior to this, how did you go about convincing your cast and crew that this was something you could pull off?

Maybe they’re crazier than I am. [Laughs]. Everyone who read the script thought it was pretty good, so that helped. While I wasn’t experienced in making feature or short films, I was quite experienced in making filmed content like ads, documentaries, that sort of thing. So I had a proven track record of telling stories. I also made a deliberate decision to seek out people who were working on their first feature film. That way, there wasn’t that sense of pessimism you might get from more experienced people. It created a great atmosphere between a group of newbies all working on their first feature together. Most of the crew were a lot younger than me — I’m 40 — so maybe it was just about finding people who were as passionate about making a film as I was. That really helped. There are only so many opportunities in Australia for cinematographers, actors, or production designers to work on a feature film because it’s a small industry. That means there are always plenty of talented people who haven’t yet had the chance to really flex their creative muscles. I think that was the main attraction for the cast and crew.

Speaking of your cast, Kate Wilson, who plays Bunny in the film, is so impressive here. Talk us through her casting, and what it was like to work with Kate as a first-time actor.

She’s really great, man. I had been working on another idea for a film — this really strange found-footage serial killer film that never got off the ground. We never did anything with it, but we did shoot a couple of scenes. The premise of the film was that these two guys, me and the main actor, were making a film about a serial killer, and we wanted actors to come in without really knowing much about what we were shooting. Kate was one of the actors, and she just understood the premise really quickly. She came into the place where we were shooting and cameras started rolling immediately. I gave her a two-minute brief. She just understood it right away. Kate has this thing where she’s withholding a little bit — you always get the sense that there’s something she’s holding back, which I really like in an actor. I think some trained actors can go a bit over the top. Kate’s actually been told by acting coaches that she needs to enunciate more and express herself more. And I tell her not to follow that advice, because what she has is this mystery about her persona. She always seems to be slightly keeping something from the audience, which I think is her main asset as an actress. Once I saw her do that weird thing, I just knew this was someone with a great onscreen presence who was also deeply professional and very mature for her age. I think she’s 21. There are scenes in Bunny that she and I rewrote on the fly while we were shooting because she’d say something, and we’d recognise that it didn’t sound quite right coming out of her mouth. There are lines in there that she came up with on the spot that are way better than anything I wrote. She’s got this incredible maturity and sense of self, and an ability to understand what a character needs without going over the top. The thing I love most about Bunny is that you see these three phases of the character, and Kate does these really subtle things — like in the middle of the film, where she’s almost like a little girl again — that really distinguish that time period from the others. I just think she’s magical.

She’s also dealing with some heavy material here, but how much fun did she have with this role, especially the more violent and bloody scenes?

It was a fun shoot overall. It was really fun. I don’t think there’s anything more fun than making a film with a bunch of enthusiastic people. It’s just the most fun you can have in the world. I think there were scenes that were tough for her. There’s a dream sequence where she’s choking on hair. Poor Kate had to stuff her mouth full of fake hair that was covered in fake blood and choke on it. That shit was disgusting — and the cast and crew made me do it at the end of the shoot too. [Laughs]. Some of those scenes were pretty tough for her. She really went through it. She’s covered in blood in some scenes, but as soon as we stopped shooting, she’d be like, “Okay, cool. What do I do next?” She also had this amazing ability to sleep on set. There were some really late nights and long days, with all this activity going on around us, and Kate would just be there having a nap. [Laughs]. I don’t know how she does that.

Ontrei as The Intruder in Bunny.

Kate’s co-star, Ontrei, who plays The Intruder in the film, brings a Heath Ledger Joker-esque edge to his performance. Was that in the brief, or was it something he brought on his own?

We discussed it. The initial script for Bunny, and the assembly cut, was two and a half hours long, while the final cut is 90 minutes. In Bunny, you’ll notice that Bunny’s watching all these old movies and VHS tapes. In the longer cut, there were many more scenes of her watching those tapes. There was also a lot more of The Intruder. His backstory was that he was also a huge movie fan, but Bunny and he have completely different tastes in films. She watches weird B-movies, vampire horror, and spaghetti post-apocalyptic films, while he’s really into Christopher Nolan movies and superhero stuff. In the longer cut, there’s a lot more of their competing visions and arguments about what makes a good movie. So Ontrei and I discussed how he built that character — how he’d shaped his personality around movie villains and styled himself after them. Heath Ledger’s Joker was certainly one of those. Ontrei drew from a variety of movie villains, and I think the Joker is probably the most identifiable influence.

And now that I know how much you love Mad Max, I also recognise Nicholas Hoult’s Fury Road character, Nux, in that performance too.

Good pickup, dude. If I could’ve painted Ontrei white, I would have. Nux is actually my favourite character in Fury Road. Weirdly, I think Nux is the emotional core of that movie. Thank you for picking that up. I’m really glad it came through.

The film’s violence is quite extreme, especially the cannibalism scenes, which are confronting. But the most horrific scene in the film is, without a doubt, the opening scene of the real footage of a bushfire’s approach. I remember seeing it on TikTok when it first dropped. How did you get access to this footage?

We told them we’re indie filmmakers and we have no money. [Laughs]. We said, “Can we please use it?” and they said yes. That footage is so shocking. The first time I saw it, I thought it was the craziest thing I’d ever seen. I watched a lot of videos from those 2019 Australian bushfires. There’s an amazing vlog by this 20-something-year-old woman who documented her daily life, and one day a bushfire hit her town. That 45-minute vlog, showing her escape, is the scariest thing I’ve ever seen. The speed with which the fire comes and the hellish destruction that follows is incredible — and then it just moves on. There’s something really monstrous about that. It’s an incredible piece of footage, and we were very lucky to get permission to use it.

The isolated location obviously plays a very important role in the film. Where did you find this house, and how easy was it to access?

It’s an Airbnb about two and a half hours southwest of Sydney. Once I wrote the script, I was like, “Shit, okay, now I’ve got to find this place.” We went far and wide looking for the perfect shack. We travelled seven and a half hours north to a different spot, but it didn’t have bathrooms, so we couldn’t shoot there. Thankfully, the guy who owned this Airbnb said yes. It’s a huge property. I want to say it’s about two square kilometres. Not only did we have that location, but we also had all this space to play in, and it was right next to a national park that had just been logged, so all the trees were flat, which looked amazing. We were actually in competition with Farmer Wants a Wife, who also wanted the location. They asked the owner if they could use it, but he gave it to us for a discounted rate instead. So we were really, really lucky.

Kate Wilson as Bunny in Bunny.

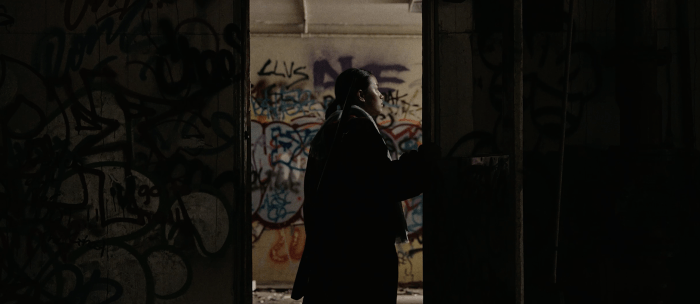

And how about the abandoned power station?

Initially, those scenes were supposed to be shot in an abandoned juvenile centre in Glebe, Sydney. I don’t know how legal it is to access, but it’s a well-known urban exploration hotspot. My daughter’s an urban explorer and she loves visiting abandoned places. So I had this huge list of properties, and we’d scouted this one several times because it was easy to get into. But on the day the cast and crew arrived to film, the whole place was boarded up, with new security cameras everywhere. Alarms went off as soon as we walked in, so we couldn’t shoot there. Luckily, we had a short Christmas break in December and January, which gave us time to find a new location which was another abandoned school in a place called Brooklyn, just north of Sydney. It was a small space, and while I was there, my daughter told me about this power station an hour further north. The day before we were due to shoot at the school, I drove up to the power station and it was magnificent. Huge, with massive open spaces. We could’ve shot there for a month. Thankfully, the owner was pretty cool about it.

The graffiti in the old power station also adds another pop of colour outside of Bunny’s house.

My initial thought was that I didn’t want any graffiti because I had this idea that the world ended quickly so who’d have time to paint? But the more I thought about it, the more I realised people probably still would. I was also conscious that I didn’t want the film to look like The Road, which is a very bleak-looking movie. I think it’s great, but I was aware that the post-apocalyptic films I like are a lot more colourful. Even though society’s breaking down, people still have valuables, they still have books, and they still might paint something. Bunny’s house is decorated with stuff she’s found. It was really important to me that, while the story is bleak, Bunny’s world didn’t look too bleak.

I know this is a cliché question, but considering this is literally your first film, what was the biggest lesson you learned making it that you’ll take into your next one?

With my next film, I’ll definitely be more ambitious with the blocking of shots. With Bunny, I was focused on getting the story and performances right with simple camera movements and angles. There were a few reasons for that which are mostly budget-related. Complicated shots take ages, which eats into your budget. We only had 19 days and a small crew, so I needed to shoot Bunny simply and effectively. Next time, I’ll aim for more ambitious blocking and camera work, and build my ability to do that while still getting strong performances. I’d also like to be more ambitious with production design and costuming.

You’ve said that you’d like to explore the world of Bunny further. How might that look?

We’ve actually written an outline of what it might look like as a TV series. There are other characters hinted at in the film, like Jimmy and the girl he’s keeping as a slave. There’s a lot to explore there: how other people in that world are surviving, thriving, or doing terrible things. We’ve got a loose outline for how that might work, whether as a sequel to Bunny or a TV show. We’re still exploring the best way to do it. I just think that an early post-apocalyptic universe is so interesting. There’s so much there to play with, from character building to story arcs. It’s an endless playground for me.

Bunny will screen at SXSW on Tuesday, October 14 and Friday, October 17. Details here. Keep an eye on cinemaaustralia.com.au for future screening details.

If you enjoy Cinema Australia as much as I love publishing it, please consider supporting Cinema Australia’s commitment to the Australian screen industry via a donation below.

I strive to shine a light on Australian movies, giving voice to emerging talent and established artists.

This important work is made possible through the support of Cinema Australia readers.

Without corporate interests or paywalls, Cinema Australia is committed to remaining free to read, watch and listen to, always.

If you can, please consider making a contribution. It takes less than a minute, and your support will make a significant impact in sustaining Cinema Australia as the much-loved publication that it is.

Thank you.

Matthew Eeles

Founder and Editor.Make a donation here.