Maggie Miles and Trisha Morton-Thomas.

Film and cultural icons in this country don’t get any bigger than David Gulpilil – one of Australia’s most loved and respected actors.

His career began with his debut in Walkabout (1971), and this seemingly unstoppable force went on to star in many classics, including Storm Boy (1976), Crocodile Dundee (1986), The Tracker (2002), Ten Canoes (2006), and Charlie’s Country (2013). Younger readers would be doing themselves a favour by exploring David’s filmography, if they haven’t already. It truly is one to behold.

While Journey Home, David Gulpilil stands on its own, it could also be considered as an unofficial follow-up to Molly Reynolds’ 2021 documentary My Name is Gulpilil, which focused on the final months of his life in South Australia. In Journey Home, David Gulpilil, filmmakers Maggie Miles and Trisha Morton-Thomas follow Gulpilil’s family as they take on the enormous challenge of fulfilling his final wish to be buried on his homeland, more than 4,000 kilometres away.

The journey was no small task. It meant travelling across crocodile-infested swamps, dealing with the tyranny of distance, and organising traditional ceremonies along the way.

Journey Home, David Gulpilil captures the sheer determination and teamwork of a family moving mountains to bring David home. Watching it, you can’t help but feel privileged to witness such a remarkable story.

Journey Home, David Gulpilil. Photo by Anna Cadden.

“I think the integrity of the relationship between Trish and I made it easier. We really did trust and listen to each other so much.”

Interview by Matthew Eeles

Journey Home, David Gulpilil is a sequel of sorts to Molly Reynolds’ 2021 documentary My Name is Gulpilil. How long after that film was it decided this one would be made?

Maggie Miles Well, there was actually a bit of an overlap. There’s a moment in our film during the Adelaide Film Festival in 2020 with Witiyana Marika. We all knew that the old man was very, very unwell and wasn’t able to make it home. Everybody in the Northern Territory just wanted him home, and we knew that Witiyana Marika would do the send-off when the time came. That little moment of the story is in our documentary. Then the old man passed away on 29 November 2021. Molly’s film had already been finished but wasn’t released until a little time after. So the first scene we filmed was that send-off, which Witiyana, as a ceremony leader, presided over on 18 December that year.

Trisha Morton-Thomas I think that because Mr. Gulpilil and Molly had already made this amazing film about his legacy and career in his own words, we were very conscious not to add to his story, because he’d already told it. It would be presumptuous of us to believe we had more to add. For us, it was always in our minds that this was the story of his family. I always try to strip away the Hollywood glamour and focus on the man. I was learning about a father, a brother, an uncle, and a grandfather, rather than a Hollywood star. So I made a conscious effort to see him as a man rather than a superstar.

How did you decide to collaborate as co-directors?

MM I really wanted to work with Trish.

TM-T Maggie came to Brindle Films, and one of the first things I said to her was, “I’ll direct this with you, but I want you to know I’m not going to be a ticked box.” That was important to me. I wanted to be part of the creative process. Maggie told me that’s what she wanted too; she didn’t want me to be a ticked box. We got along really well. There were times it was tense, but we backed each other. Maggie, do you agree?

MM A hundred percent. And I think the intensity was a great thing, because you’ve got to be rigorous with the process and with each other. There’s also that extra level of scrutiny with co-directing, which I fully embraced on this film, especially because we were working very closely and intensely with key family members. I also remember some of the conversations Trish and I had. I might be asking something that wasn’t a literal element of the story, but for me it was this question: What was the cost to the old man of having to leave his community, his culture, and his family to be a movie star? Because Trisha has also, at times, had to leave her family and culture to do her creative work, we had some really good conversations about that, which were very informative for me.

Before we get too deep into the making of this film, I want to ask you both about your first introduction to David, either on screen or in person.

TM-T For me, it had to have been Storm Boy. I can’t remember a time in my life when Gulpilil wasn’t on screen. I also had the pleasure of knowing Rosalie Kunoth-Monks, who people will know as Jedda. But yes, definitely Storm Boy.

MM I watched Walkabout when I was about 14, at high school in a village in the middle of England. Off-screen, when I was living and working in Darwin, our company, Burrundi Pictures, supported our director in making all the early film clips for the band Yothu Yindi. That’s when I first met Witiyana Marika. We were all working together on a feature film called Yolngu Boy, which I also cast. We had a big workshop for all the teenage boys and girls as part of that process, and David came in to support and encourage everyone. There were about 16 young adults vying for a part in Yolngu Boy. He talked, he danced, and he totally captivated everyone in the room. That was the first time I met him in person.

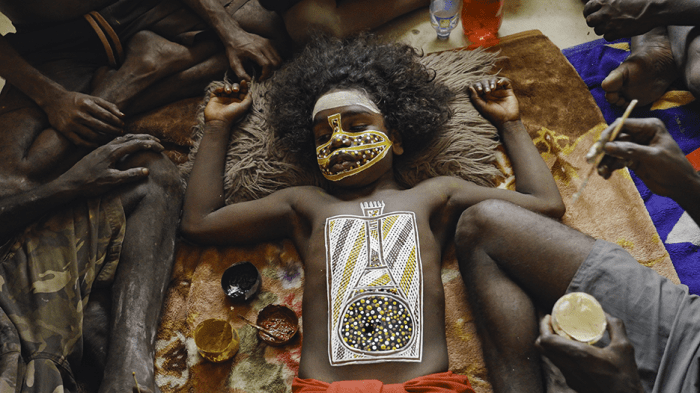

Journey Home, David Gulpilil. Photo by Anna Cadden.

There are some truly emotional and confronting moments in this film. Considering your connections to David, how did you balance your emotions during the shoot, or did you just surrender to them?

TM-T For me, it was a lot harder. I lost my own brother while we were filming. We had our own ceremonial obligations to bury him. At times, the film hit really hard. I felt like I couldn’t breathe. But I had this incredible team around me: Rachel Clements, Maggie, Bridget May, and others who came and went from the project. They held me up when I felt like I couldn’t face another day. There were parallels between what was happening on screen and in my personal life. Sometimes I had to say to Maggie, “You’ve got this one on your own. I trust you, and you need to run with it.”

MM I think the integrity of the relationship between Trish and me made it easier. We really did trust and listen to each other. The first time I saw that raw emotion was on a really hot day when I was filming. I actually filmed about a third of this documentary — which sort of embarrasses me! The day the old man’s body was repatriated from Darwin on Larrakia Country and flown to Ramingining, then taken to the Nhulunbuy mortuary, was massive. It was so hot. We landed on the tarmac in Ramingining, and the ABC crew was there. I was filming for the doco, and all of a sudden the ground started trembling. The women were grieving as they do, and I thought, Oh my God. You could feel the grieving process through your feet. I wondered, Should I be filming this? But everyone was so welcoming to us. That day, we had the official nod from Jida, the eldest son, who was happy with what he’d heard about the film and our approach. Witiyana Marika was the first person to invite us in, and through those relationships, all the family said, “We want to show you. We want to let you into this world. In that way, we can talk about it.” We were delighted that by filming it, we could let everyone else witness it too.

I certainly felt honoured to be witnessing it. And that leads me into my next question, which is that these processes are rarely seen on film, if ever. What discussions were had with David’s family about what could and could not be filmed?

TM-T It’s a moment-by-moment process. People have given you permission to film, but if you start moving into a space where they don’t want the camera, they let you know. And if you’re being respectful, you listen and you move away from that direction. But I think, generally, it was pretty open for us. The family really did want to honour Mr. Gulpilil’s wish that the rest of the world attend his funeral, so I think they opened those doors to us.

MM And those lines of communication, and that trust that builds through relationships and friendships, is so important.

TM-T That’s the main thing, building that trust. Maggie’s relationship with them was already established through other projects. And I’m quite happy to say, and I always say this in regard to this particular film, Maggie could have made it without me. There’s no way I could have made it without Maggie. And that’s quite simply because of her connections to that community and the relationships she’s built over years with that family.

MM Trish, do you remember the day after the main funeral shoot, when we’d gone up to Ramingining to do some research? We won’t go into the long story of the really great journey, but it was five hours in a car, trekking through these little goat tracks. We thought we might get there late, so we threw our blankets and pillows in the car, and we took Joyce’s [Malakuya Mailbirr, executive producer] little grandson with us, along with another of the aunties. When we got to Joyce and Peter’s house, everybody wanted to talk to us about the old man straight away. Literally, there were fifty or sixty people just sitting around, and we were showing our footage. That’s when we learned about one beautiful man, who had since passed away, who was in the footage. We instantly asked, “Would you like us to edit around this gentleman? Would you like us to leave him out?” And this amazing conversation happened. Like Trish said, it’s moment-by-moment. That man’s sisters were there, so the appropriate people asked the other appropriate people, and they said, “This is our memory of that moment, and it’s there for the next generations of children who will see what we did. So we are comfortable with you leaving him in.”

TM-T Actually, when you look back over the years that this film was shot, there are a few young people in there who are no longer with us, and their families have been very, very generous in allowing us to keep the film that way.

Journey Home, David Gulpilil. Photo by Allan Collins.

How often does a cultural undertaking like this happen on this scale?

TM-T It actually happens quite a lot. There were many, many families right across Australia during COVID which this kind of undertaking happened to. We’ve had to bring my sister back from Queensland. We’re constantly trying to bring people back home. But within the Central Desert, we don’t have croc-infested rivers like they do up north, so we’re really lucky. [Laughs]. But I have heard of people bringing others home. I don’t know if it’s been on this scale.

MM That’s a good point about the environmental factor. The family had the environmental factors to wait for as well. The access points were being covered up by the swamp, so they were waiting and waiting and hoping for the ground to be dry enough to drive him from Ramingining all the way back to his homeland, which wasn’t possible in the end. So even though I know that many funerals are big, I personally haven’t seen just the expedition—the huge mission—that took place here. The family makes it look seamless as well.

TM-T They make it look like it’s just a walk in the park. [Laughs].

The complexities of David’s final journey are so well documented in great detail here, but I’d love to know about the complexities of the filming process.

TM-T Not so much for me, but I’ve heard that Maggie has actually been on shoots that have been nightmares. I’ve sort of rocked up and it’s all happy sailing. [Laughs]. They’ve had to fly through cyclones and everything to get to a shoot.

MM: I’ll give you the short story, because it’s Allan Collins’ [director of photography] story to share. In Ramingining, beginning in the dry season, you drive across the bush for about 45 minutes. You drive across that swamp for about half an hour. Then on full tide, you go over what we called Gupulul Crossing—it’s got crocodiles in it. And in low tide, you’ve got to drag the boat through the mangroves with mud up to your knees, and then you walk for an hour and a half, and then you’re at this old house of the old man’s in the bush, which is a shell of a house. There’s no kitchen as such, no running water, no toilet, no bathroom, no gas, no electricity. So when you’re there, you camp. Allan hadn’t been there before. We took him in to start filming. We got the logistical setup happening, and we sent Anna [Cadden, co-cinematographer] and Jack [Rule, production assistant] there early so they could film a couple of things. Then Allan got to fly in the chopper because he was doing some important filming on the way, of course. [Laughs]. We were meant to be there for two nights, but then the family weren’t ready to bury the old man yet. They had more things to do, more people coming. Most of our crew had to go because we were working on development funding at the time, and everyone had other jobs to get to, and we had no more money. So everybody left. Then it was just Allan and me. I kept everyone’s food, everyone’s water, all the belongings. We had this little generator. We filmed through Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, and out on Friday morning. It wasn’t until we left in the car that Allan went, “What? Where am I?” Because you can’t drive out of there. There aren’t any roads. You need someone with a boat to get across the river. That was one of the challenging aspects of being out there. But I’ve got to say, it was one hundred percent adventure. And all the families, I would look at those women, and they’re just incredible. I thought, “Well, if they can keep going under these tough conditions, nothing’s going to stop me.”

Journey Home, David Gulpilil. Photo by Allan Collins.

As a viewer, their sense of adventure certainly is one of the great aspects of this documentary, that’s for sure. And at the same time, the film is also brimming with these beautiful, heartwarming, and often breathtaking moments. What were some of the most memorable moments of this shoot for you, that weren’t so much of a challenge?

TM-T For me, there are so many parts of this film that are really, really beautiful. But there were moments off camera where you’re just talking to family and hearing these stories—family talking about Mr. Gulpilil from when they were little, or even teasing each other. I am Aboriginal, but I’m Aboriginal from a different culture, so I was sitting down with this mob in the Top End who are my neighbours, but I don’t really know a lot about them. It’s almost like sitting me down in France. The difference in culture is that big from my own, but there are similarities as well. For me, it was learning what was similar, but also reflecting on this very, very different culture to mine. I just absolutely adore Mr. Gulpilil’s sister, Evonne. She’s beautiful, and I spent a lot of time sitting with her.

Did any of those stories catch you by surprise?

TM-T Well, there’s a lot of stuff. We know that Mr. Gulpilil wasn’t a good boy, so there was a lot I learned about other families or tribes that were not happy with him. But that wasn’t really part of the film or this story. This film really was about his family and his community, who were just fulfilling a promise to him.

MM I’m thinking about Lloyd Gurrawurra. He’s got the cheekiest smile, and he’s funny as hell in this film. The relationships, how people look after each other in the communities, are incredibly complex, very binding, and very interesting. Lloyd was given the responsibility to help the family plan the funeral. He’s the eldest grandson, but he’s also interested in filmmaking. We got to the stage where we realised, as well as having the cultural storytelling by the wonderful rapper Danzal Baker, or Baker Boy—who was amazing for the family—it was also a question of how we could fit Baker Boy in, because everybody in the film connects back to the old man in some way. One of Danzal Baker’s grandmothers lived in the Arafura Swamp and was actually a promised wife to the father who grew David up. That was an extraordinary connection. We asked Lloyd, “We really do need a narrator from the family point of view. Who would you love?” He and his cousins all have such a strong love for the great Hugh Jackman, who David formed a really, really strong relationship with on the set of Australia. We were able to go to Hugh and say that, by request of the family and the eldest grandson—who had this responsibility to bring aspects of the funeral and therefore the film together—would he consider it? And he came on board straight away because of the respect he had for David.

TM-T: I remember saying sarcastically, “Oh sure, we’ll just give Hugh Jackman a call and ask him to narrate it.” [Laughs]. But it happened. It’s always worth reaching out to these people.

Journey Home, David Gulpilil is set for a major run on the Australian film festival circuit. Here’s where you can catch it:

Melbourne International Film Festival from Saturday, 16 August. Details here.

CinefestOZ from Monday, 1 September. Details here.

Darwin International Film Festival from Thursday, 11 September. Details here.

If you enjoy Cinema Australia as much as I love publishing it, please consider supporting Cinema Australia’s commitment to the Australian screen industry via a donation below.

I strive to shine a light on Australian movies, giving voice to emerging talent and established artists.

This important work is made possible through the support of Cinema Australia readers.

Without corporate interests or paywalls, Cinema Australia is committed to remaining free to read, watch and listen to, always.

If you can, please consider making a contribution. It takes less than a minute, and your support will make a significant impact in sustaining Cinema Australia as the much-loved publication that it is.

Thank you.

Matthew Eeles

Founder and Editor.Make a donation here.