Indigenous Australian’s holistic and interconnected ways of experiencing wellbeing is brutally disrupted by British colonisers, leading to negative intergenerational trauma and systemic disadvantage.

Luisa Mitchell’s Our Wellbeing, Our Way (OWOW) is a dramatic journey from our ancient past to our living present. For over 60,000 years, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have lived in harmony and balance with the natural world in the land that is now known as Australia.

In the film, a young Aboriginal family sitting around the campfire yarning stories represent the continual and flowing peace that has existed for our people since time immemorial, as they are fully connected to their family, kinship, country, and spirituality. But that carefully developed system of wellbeing is brutally disrupted when a grandmother and granddaughter witness the invasion of their lands by empire and industry-driven British colonisers in the late 18th century. Bringing with them violence, disease and displacement,colonisation leads to the loss of many Aboriginal people’s lives, including the girl’s grandmother.

Lost and alone, the young granddaughter grows up in a time of significant upheaval – including losing her child to what is referred toas the Stolen Generations, where Indigenous children were forcibly removed by government officials. Now an old woman, her life is symbolic of what many Indigenous Australians have experienced: intergenerational trauma, loss of culture and kinship, connection to Country, and brutal discrimination and abuse. The woman, now trapped in a cycle of systemic disadvantage as she lives out her last days on a mission reserve, loses all hope of a better future for her people. Any memory of the harmonious system of wellbeing,so important to First Nations people for thousands of years, has seemingly faded away…

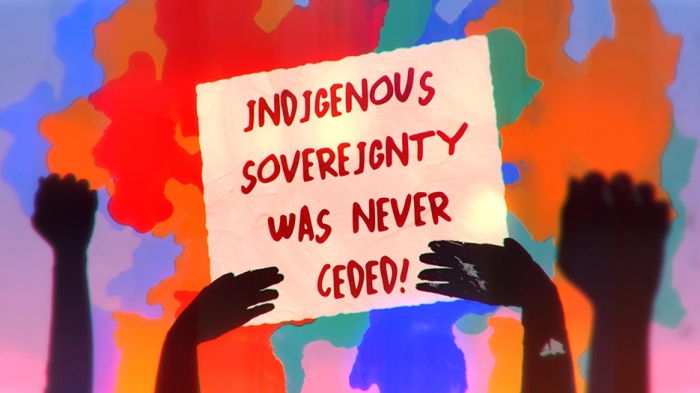

But a young activist witnessing these atrocities begins to paint down his feelings of anger and injustice onto canvas. Soon, a growing number of First Nations people join him in the land rights and social justice movement, swelling into large public protests and calls for equality. With force in numbers, public policy begins to shift towards humanitarian outcomes, including land rights and healthpolicy reforms. The old woman we saw grow up during the invasion of her country is reunited with her son, who was taken from heras a boy.

While some human rights progress is achieved for First Nations Australians, we see that the journey to healing is ongoing, as the issue of systemic disadvantage and discrimination is still as prevalent today as ever. A male and female Elder, wise with years of teaching culture, share their advice on how Australia as a nation can continue to work alongside and in support of First Nations people to bring about a balance of social and emotional wellbeing for their people – just as it once had been for their ancestors since the beginning of time.

Luisa Mitchell.

Why I made Our Wellbeing, Our Way

by Luisa Mitchell

I am a producer, writer and filmmaker originally from the remote northwest town of Broome in Western Australia. I was privileged to grow up in a multicultural town that embraced its traditional Yawuru and Djukun (Aboriginal) language groups as well as its historical ties to Asia, particularly Japan, Philippines, and Malaysia. My own heritage is Whadjuk Nyungar, a clan from the southwest of WA in what is now known as Perth, and colonial settler European. I have always been drawn to telling stories that bring me closer to my own Nyungar family and identity, as well as celebrate our being the oldest surviving culture in the world. Over thousands of years, the hundreds of tribes that make up Indigenous Australia have carefully and strategically curated a system of living and understanding that ensures both perfect harmony and balance with the natural world, and within themselves. This was and is achieved through marriage and kinship systems, totemic practices, traditions of responsibility and protection towards mother earth, and beliefs in spirits and ancestors who gave guidance through stories and songs.

When I was approached by the Centre of Best Practice in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Suicide Prevention about creating a short film on Indigenous social and emotional wellbeing, I knew that I needed to tell audiences a much bigger story about our shared history – of this balance that existed before colonisation, and how badly it has continued to be damaged as a result of it. Indeed, this couldn’t just be a historical film; as colonisation is an ongoing process that is impacting First Nations mob today, it was important to reflect on current injustices and pathways to healing for the future. Due to the decades-sweeping scope of the story, and the subject of the film heavily reflecting on themes of harmony with nature and wellbeing, I chose to use a rough, free-hand animation style (by animator and co-director Radheya Jegatheva) that appears as if it is constantly moving – across time, across characters, across the different domains of wellbeing – whatever it was, I didn’t want this film to be visually stagnant, and few shots are ever truly still.

“By recognising our society’s duplicity in colonisation and this system we have built, that simply does not work for Indigenous Australians, we can come together to forge strong solutions for an equitable future.”

The colour palette chosen also symbolised Country, that which ties all First Nations principles together: oranges and reds of earth, dust and blood; black of people and the night sky; blues of oceans, rivers and waterholes; and yellow of the sun, life and hope. I also decided to take a dramatic storytelling lens to what could have otherwise been a dry informational video on health and share this nation’s history through a few key characters: the young woman living through colonisation; the grandmother in the missions, broken from trauma; and the old man who teaches his grandson lessons for a better future. These characters are at moments interchangeable, though years have passed and they reflect a different time period in history. This was done purposefully to reflect our ways of viewing time as being a circular construct and living thing – past, present and future intermingling.

I had two key messages I wanted to articulate with this film. The first was that the strong emotional sense of brokenness and distress felt by Indigenous Australians is not tied to a distant past, but being felt today, and is therefore a responsibility of all Australians to end the causes of those symptoms. The second was that health and wellbeing for Indigenous Australians is so much bigger than just mental and physical health – it is holistic and highly complex, relating to principles of kinship, country, spirituality, and other factors. In this regard, I want audiences to understand that a one-size-fits-all approach to Indigenous health will never be successful at removing the long-standing issues our communities face, such as lower life expectancy, higher disease morbidity, and staggering rates of death by suicide. Yet the film finishes on a message of hope and unity: by recognising our society’s duplicity in colonisation and this system we have built, that simply does not work for Indigenous Australians, we can come together to forge strong solutions for an equitable future.

Our Wellbeing, Our Way will screen at the Melbourne Documentary Film Festival in July. Details here.

If you enjoyed reading this feature article as much as I loved publishing it, please consider supporting Cinema Australia’s commitment to the Australian screen industry via a donation below.

I strive to shine a light on Australian movies, giving voice to emerging talent and established artists.

This important work is made possible through the support of Cinema Australia readers. Without corporate interests or paywalls, Cinema Australia is committed to remaining free to read, watch and listen to, always.

If you can, please consider making a contribution. It takes less than a minute, and your support will make a significant impact in sustaining Cinema Australia as the much-loved publication that it is.

Thank you.

Matthew Eeles

Founder and Editor.